Botswana’s war on its indigenous population, the Bushmen of the Kalahari, has reached a new pitch, writes LEWIS EVANS. No longer content to arrest and intimidate them as they engage in subsistence hunting on their own land, the state has begun to shoot them from aircraft. These illegal, genocidal acts must stop!

Botswana police scour the Kalahari, looking for people hunting with spears to intimidate and arrest. Planes with heat sensors fly over the Bushmen’s lands looking out for ‘poachers’ – in reality Bushmen hunting antelope for food.

In a healthy democracy, people are not shot at from helicopters for collecting food. They are certainly not then arrested, stripped bare and beaten while in custody without facing trial.

Nor are people banned from their legitimate livelihoods, or persecuted on false pretenses.

Sadly in Botswana, southern Africa’s much-vaunted ‘beacon of democracy’, all of this took place late last month in an incident which has been criminally under-reported. Nine Bushmen were later arrested and subsequently stripped naked and beaten while in custody.

The Bushmen of the Kalahari have lived by hunting and gathering on the southern African plains for millennia. They are a peaceful people, who do almost no harm to their environment and have a deep respect for their lands and the game that lives on it. They hunt antelope with spears and bows, mostly gemsbok, which are endemic to the area.

According to conservation expert Phil Marshall, there are no rhinos or elephants where the Bushmen live. Even if there were the Bushmen would have no reason to hunt them. They hunt various species of antelope, using the fat in their medicine and reserving a special place for the largest of them, the eland, in their mythology. None of these animals are endangered.

A shameful history of state persecution

Despite all this the Botswana government has used poaching as a pretext for its latest round of persecution. The increasingly authoritarian government of General Ian Khama sees the Bushmen as a national embarrassment. It wishes to see them forcibly integrated with mainstream society in the name of ‘progress’.

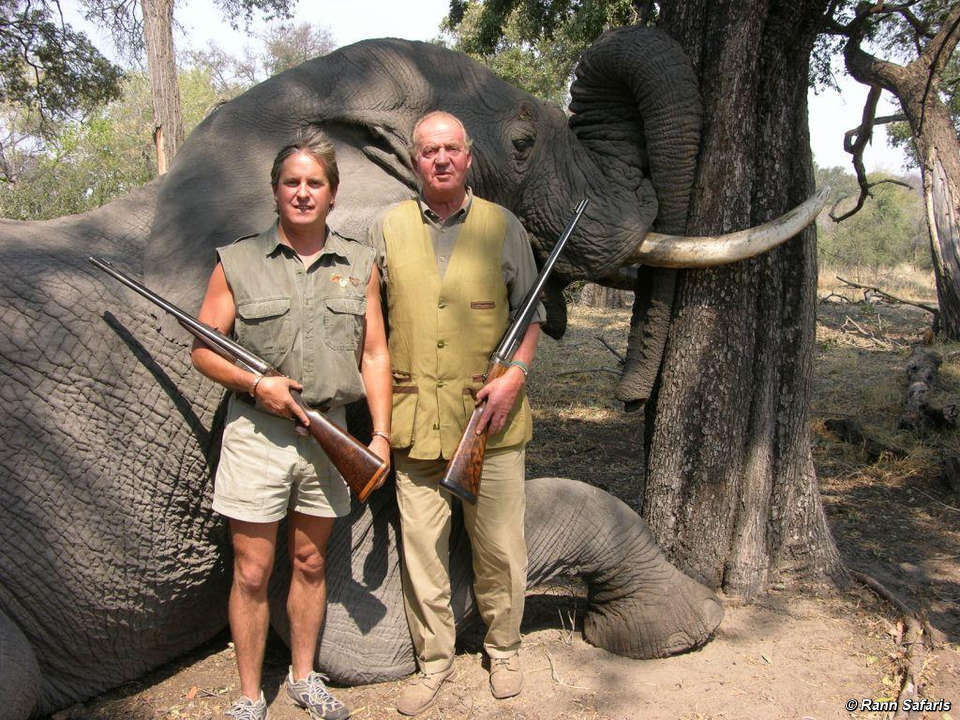

There are huge diamond deposits on, or close to, the Bushmen’s lands, as well as natural gas which is soon to be fracked out of the soil. Botswana would rather see wealthy foreign tourists on the Bushman’s lands – many of them western trophy hunters – as well as foreign corporations digging for resources underneath it. In their eyes, ‘primitive’ hunter gatherers are an inconvenience.

Between 1997 and 2002, hundreds of Bushman families were brutally evicted from their land in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. Their homes were destroyed, their wells were capped, their possessions were confiscated, and they were moved to government eviction camps en masse. Any who tried to resist were beaten, or even shot with rubber bullets.

There are close ties between the Botswana government and the infamous De Beers diamond corporation, and both have grown rich from the gemstones. Nevertheless, the government was savvy enough to know that diamonds alone would be an ugly excuse for wiping out an entire people, so they circulated absurd rumors.

The Bushmen were ‘poachers’, they said. They rode around in jeeps, they shot game on a massive scale with rifles, and posed a threat to the environment they had been dependent on and managed for millennia. They had to change, for the sake of ‘civilization’.

Despite a landmark court ruling in 2006 which the Bushmen won with the support of Survival International, the situation is still pretty terrible. Most of the Kalahari Bushmen are still living in government camps, and access to the Reserve has only been granted to a limited number of individuals. It is enforced under a brutal permit system, which sees children born in the reserve forced from their homes and family at the age of 18.

The permits are not heritable, and so when the present generation of Bushmen dies, their people will have effectively been legislated into extinction. The system was compared to the apartheid-era South African pass laws by veteran anti-apartheid activist and former Robben Island prisoner Michael Dingake.

The annihilation of a people – genocide in open sight

As if that wasn’t bad enough they aren’t even allowed to hunt to eat. In 2014, Botswana introduced a nationwide hunting ban, but gave a special dispensation to fee-paying big game hunters, who flock to the northern Kalahari and the Okavango Delta in the extreme north of the country to shoot animals for sport.

Such a dispensation was not extended to the tribal peoples who actually live in these territories, who are accused of ‘poaching’ and face arrest, beatings and torture while tourists are welcomed into luxury hunting lodges.

And now they are being shot at from helicopters. Botswana police scour the Kalahari, looking for people hunting with spears to intimidate and arrest. The government has introduced planes with heat sensors to fly over the Bushmen’s lands looking out for ‘poachers’ – in reality Bushmen hunting antelope for food.

Police and wildlife officials then use whatever brutality they consider to be necessary to enforce the ban.

This is an urgent and horrific humanitarian crisis. An entire people’s future is at stake. If the Bushmen cannot enter their land or find food there, they will have no option but to return to the government camps, where vital services are inadequate and diseases like HIV/AIDS run rampant.

Policies like this have been used by governments all over the world. It is easier and less shocking than simply exterminating people, but in the long-term it has a similar outcome. By denying people their land and basic means of subsistence, viable ways of living are abolished, and peoples’ land, resources and labor are stolen.

In a world of larger-scale and more headline-friendly crises, the plight of the Kalahari Bushmen risks being largely ignored. Nevertheless, the Bushmen – portrayed as backward and primitive simply because their communal ways are different – could face annihilation if the brutal shoot on sight policy is left in place.

Lewis Evans is an author, and a campaigner at Survival International, the global movement for tribal peoples’ rights.