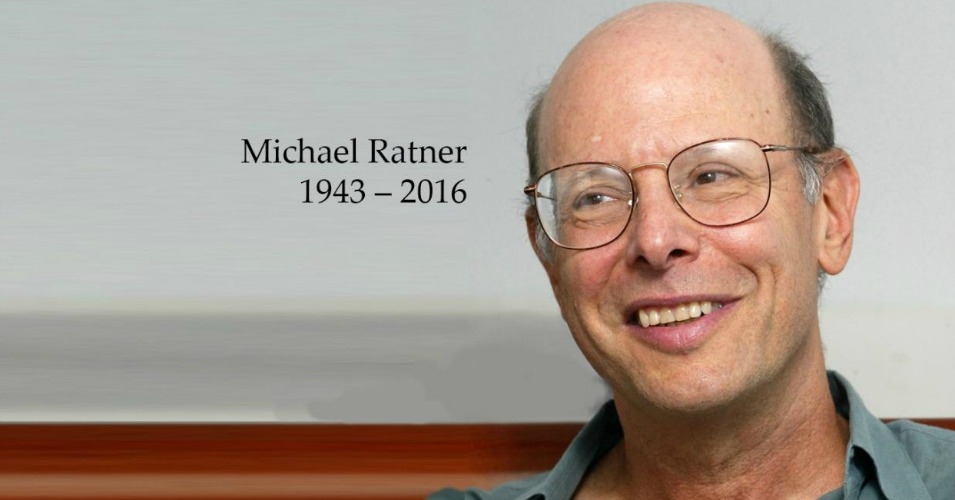

Several years ago, I asked the civil-rights lawyer Michael Ratner, who died Wednesday at age 72, whether he thought he had any chance of prevailing when, with the Center for Constitutional Rights, he sued George W. Bush in early 2002 on behalf of some of the first Guantánamo detainees. “None whatsoever,” he replied. “We filed 100 percent on principle.”

The law was against him; the Supreme Court had ruled in World War II that prisoners of war could not challenge their detention in US courts. And the politics were even worse; the World Trade Center cleanup was still ongoing, the detainees had been declared “the worst of the worst,” and, as alleged foreign terrorists, the detainees elicited little sympathy from Americans. But to Ratner, challenging the president was the right thing to do, and that was enough. Ratner made a career of suing the powerful. He sued Ronald Reagan for funding the contras in Nicaragua and invading Grenada, George H.W. Bush for invading Iraq without congressional authorization, Bill Clinton for warehousing Haitian refugees with HIV at Guantánamo Bay, and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld for torture. He sued an Indonesian general, a Guatemalan defense minister, and a Haitian dictator, among others, for human-rights abuses. He sued the FBI for spying on Central American activists and the Pentagon for restricting press coverage of the Gulf War. The pattern was set early: His very first federal lawsuit was styled Attica Brothers v. Rockefeller, and sought to compel New York to prosecute state police responsible for killing prisoners at Attica State Prison after riots broke out there in 1971.

Ratner knew that when you sue the powerful, you will often lose. But he also understood that such suits could prompt political action, and that advocacy inspired by a lawsuit was often more important in achieving justice than the litigation itself. He understood the inextricable links between advocacy in court and out. Consider, for example, his greatest victory—the Supreme Court’s 2004 decision in Rasul v. Bush, declaring that Guantánamo detainees had a right to seek judicial review of the legality of their detention as “enemy combatants.” As soon as Ratner filed the first habeas corpus petition on behalf of Guantánamo detainees, in 2002, he began working with Gareth Peirce, Clive Stafford Smith, and other British lawyers to build public support in the UK for his clients, several of whom were British. He understood that the British public would be more sympathetic to the plight of British detainees than would Americans, and that British public opinion could be a useful prod to American action. The public outcry in the UK forced Prime Minister Tony Blair, initially a full-throated supporter of Bush’s Guantánamo policy, to reverse himself and demand that the British detainees be released.

Once Blair reversed his position, Bush released several of the British detainees, including some of Ratner’s clients. And upon their return to the UK, the detainees immediately went public with accounts of the torture they had suffered there. Those stories traveled across the Atlantic, and when the first “enemy combatant” cases were argued in the Supreme Court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked the government’s lawyer about torture, even though the issue was not presented by the case. Bush’s lawyer, Paul Clement, assured the Court that the government would never torture. That evening, CBS’s 60 Minutes 2 broadcast the first photos of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. The Supreme Court went on, in Rasul v. Bush, to reject Bush’s argument that he had unreviewable authority to detain in the “war on terror,” marking the first time in history that the Court ruled against a president during wartime on the treatment of enemy fighters. In significant part because of pressure sparked by that victory, by the time Bush left office, he had released more than 500 of the 779 people he had imprisoned at Guantánamo.

He was the catalyst for countless lawsuits, but he rarely took the role of lead counsel, letting others take credit.

Lawyers tend to be cautious, by temperament and training. Not Ratner. He pursued justice fearlessly in the face of daunting odds. Lawyers also often have large egos. Again, not Ratner. He was the catalyst for and brains behind countless lawsuits, but he rarely took the role of lead counsel, comfortable standing back and letting others take credit. In this respect, he was the consummate mentor, giving countless younger lawyers, myself among them, the guidance and responsibility that inspired us to follow in his footsteps. And he never overestimated the importance of lawyers in movements for social justice. He saw law not as the sole or even primary means of achieving change, but as just one tool among many. For someone so willing to file bold challenges against the most powerful officials, he was remarkably humble about the part he played, and the part that law itself played, in the wider struggle.

In an era of globalization, Ratner adapted the tactics of the classic civil-rights lawyer to concerns about global justice. Many of his lawsuits challenged US interventions abroad, especially in Central America. He pioneered the use of the Alien Tort Statute, a law enacted in 1789, to bring human-rights claims in US courts for torture and other grave human-rights abuses. He invoked the principle of “universal jurisdiction,” which permits countries to prosecute torturers wherever they are found, to pursue accountability for US torture in German, Spanish, and French courts, when US avenues were blocked. In the latter cases, he did not prevail. But as he would have put it, “We filed 100 percent on principle.”

DAVID COLE, legal affairs correspondent for The Nation and a professor at Georgetown University Law Center, is the author, most recently, of Engines of Liberty: The Power of Citizen Activists to Make Constitutional Law (April 2016)