Western media focused intently on a Russian “murderer” released in the exchange with Washington, but whitewashed the record of his target – a Chechen militant now confirmed as a CIA asset.

August 1 saw the largest prisoner exchange between Moscow and Washington since the end of the Cold War. Among those freed were Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and former US marine Paul Whelan, who were each serving 16 year sentences for espionage.

In the other direction, Russian opposition activists jailed for criticism of the so-called “special military operation” have now resettled in Western countries. This includes politician Ilya Yashin, sentenced to eight-and-a-half years in December 2022. At a press conference in Bonn, Germany on August 2, he described the feeling of being beside “the wonderful Rhine river”, when just a week earlier he was imprisoned in Siberia, as “really surreal.” But Yashin claimed that his release was difficult to personally accept, “because a murderer was free.”

He referred here to Vadim Krasikov, a Russian convicted of killing the Georgian-born Chechen militant Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Berlin in August 2019, who was also released as part of the deal. He was reportedly of extremely high value to the Kremlin. In a February 2024 interview with US journalist Tucker Carlson, Russian President Vladimir Putin proposed trading Gershkovich for an unnamed Russian “patriot” imprisoned in a “US-allied country” for “liquidating a bandit.”

Krasikov was that “patriot”, and Khangoshvili that “bandit.” In 2004, Khangoshvili led a lethal guerilla operation that killed four Russian soldiers. Krasikov was tasked by the Russian state with serving the Chechen justice, cutting him down in broad daylight in Berlin in 2019.

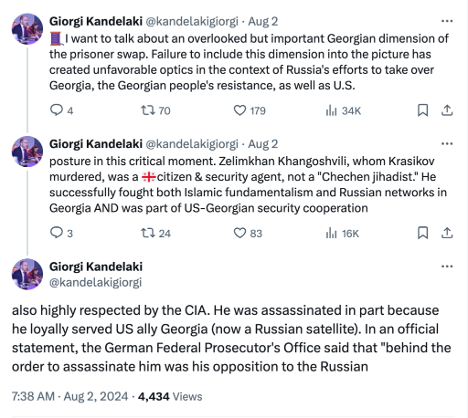

While the Russian operative has been subject of intense mainstream interest since the swap, the media has largely whitewashed Khangoshvili’s background. To the extent he was mentioned at all, he was laconically characterized as a “Chechen militant,” or more favorably, as a “dissident.” For some anti-Russian ideologues, the Western media’s failure to completely lionize Khangoshvili demanded a rebuke. Giorgi Kandelaki, formerly a Georgian lawmaker with the United National Movement of the now-imprisoned former President and US posterboy Mikheil Saakashvili, was so repulsed he took to ‘X’ to correct the record.

Kandelaki seethed that Khangoshvili was, in fact, a patriotic Georgian citizen and state “security agent.” What’s more, he was “part of US-Georgian security cooperation,” and “highly respected by the CIA.” The furious former MP suggested Khangoshvili “was assassinated in part because he loyally served” Tbilisi at a time when it was an effective US colony under the puppet Saakashvili’s rule.

By attempting to heroize Khangoshvili, Kandelaki highlighted an inconvenient truth, one which has been heavily concealed and consistently denied: the CIA covertly supported fundamentalist Chechen separatist militias while they fought consecutive guerrilla wars against Russian rule during the 1990s and early 2000s, carrying out atrocities against civilians and prisoners of war alike.

The Western media’s refusal to acknowledge Khangoshvili’s US intelligence connections reveals that a coverup of this sordid, clandestine history remains ongoing today.

Chechen agent worked for multiple Western spying agencies

A September 2019 Daily Beast report by neoconservative operative Michael Weiss provided details on Khangoshvili’s alliance with the CIA, and his Chechen war history. Describing him as “a battle-tested veteran” of those conflicts, he reportedly “commanded enormous respect” from ethnic Chechens residing in Georgia’s Pankisi Gorge. Khangoshvili was also “a close confidant” of Aslan Maskhadov, Chechnya’s separatist president, killed in a March 2005 FSB raid. He also enjoyed an extremely warm relationship with Western spying agencies.

According to Weiss, “American counterterrorism officials not only found Khangoshvili’s intelligence credible and useful,” but recruited new Chechen agents based on his assessments. These assets were subsequently “sent abroad by the CIA.” Simultaneously, he informed “on members of his native community” in Georgia. Oblique reference is also made to his “six-year stint as the valued asset of a European security service,” and how his residence in Berlin was “located right across the street from the headquarters of the BND,” Germany’s foreign intelligence agency.

Unmentioned in that report, Khangoshvili commanded a violent June 2004 takeover of the Ingusethian city of Nazran by Chechen militants. Dozens of Russian security officials were killed, including senior FSB officers. He was resultantly placed on a list of 19 wanted “terrorists” that Moscow shared with Western authorities, although recipient and host governments alike refused to turn any of them over, raising the Kremlin’s ire. German investigators allege Khangoshvili’s murder was intended to send a clear message to those who cross Russia hiding abroad.

Whether the attack was in any way coordinated with, or even funded and directed by the CIA, remains an open question. At this time, Khangoshvili’s native Pankisi Gorge has been confirmed by the BBC to have provided refuge to Chechen separatist fighters, serving as a key staging ground for attacks on, and means of getting fighters and supplies into, Russia.

In 2002, Moscow threatened to carry out cross-border strikes on the area as a result. Georgia responded by pledging to reestablish order in the area, and invited US military advisers to assist in the mission. But as journalist Mark Ames has reported, Washington’s actual objective was to train Tbilisi’s forces in “key imperial outsourcing duties” and complete the country’s transformation into “a flagship franchise of America Inc.” The benefit for Georgia was “Russia wouldn’t fuck with them.” This perceived invincibility surely encouraged Chechen militants, including CIA asset Khangoshvili, to continue their activities apace.

Khangoshvili’s status as a “close confidant” of Aslan Maskhadov is similarly striking, because the Chechen separatist leader determinedly sought CIA support for his anti-Russian jihad. His right hand man, the Chechen militant and separatist activist Ilyas Akhmadov, has revealed that before visiting Washington in early 2001 for “low-profile” meetings with US officials, Maskhadov suggested he approach “large organizations that have huge capacities,” such as the CIA, to “help the Chechen cause…much as it helped the Afghans against the Russian invasion in 1979.”

“[Mashkadov] believed that the CIA, which had sent aid to Bin Laden…still had influence over them. Believing this, he thought the CIA could persuade various Muslim organizations abroad to send financial help,” Akhmadov has written. “I remembered he once said to me, referring to the United States, ‘Why don’t they send me the money? I’ll prove to be a very reliable partner.’”

Terror trail begins in Bosnia

Akhmadov claims he never met with the CIA during his visit to Washington. He nonetheless secured asylum in the US in 2004, despite intense Department of Homeland Security opposition, due to his militant past. The following year, the National Endowment for Democracy – a US government regime change front – provided him a fellowship. Akhmadov’s federally-funded mission was “to focus international attention on the humanitarian tragedy in Chechnya.”

In the meantime, multiple “Muslim organizations abroad” had become the subjects of criminal investigations in the US for providing financial assistance and much else besides to Chechen militants – just as Maskhadov desired. For years prior to 9/11, the FBI closely monitored the activities of US-based Islamic charities and relief organizations which, under humanitarian cover, funneled fighters, weapons, and money to numerous “jihads” across the globe.

No action was taken against these entities, in part because they were assisting fundamentalist fighters in US-directed proxy wars in countries such as Afghanistan. After 9/11, however, authorities moved quickly to proscribe their activities, and indicted their founders and staff on serious terrorism charges. Among them was the Benevolence International Foundation (BIF). In October 2002, its Syrian-American director Enaam Arnaout was charged with “providing material support to Al Qaeda and other violent groups” in Bosnia, Chechnya, and elsewhere.

Arnaout’s indictment painted a lurid picture of an individual and organization intimately connected with Bin Laden, explicitly encouraging “martyrdom.” He was alleged to have personally facilitated transport of senior Al Qaeda personnel to theaters of combat, by disguising them as BIF staff, and faced 90 years in jail as a result. Yet, in February 2003 he entered a plea agreement with prosecutors whereby he pleaded guilty to a relatively minor, single count of defrauding BIF investors, by concealing from them that:

“A material portion of the donations received by BIF based on BIF’s misleading representations was being used to support fighters overseas.”

In return, Arnaout received a mere decade-long prison sentence. Given the hype and sensationalism that had attended his indictment, and the accusations of US officials, the media was stunned by his light treatment. A contemporary New York Sun editorial suggested authorities sought “to avoid a risky trial” that they may have lost, had the terrorism charges against the BIF chief remained.

However, the court’s ruling acknowledged Arnaout avowedly provided boots, tents, uniforms, x-ray machines, ambulances, walkie talkies and other resources specifically for use by extremist, Al Qaeda-linked fighters. This did not elicit terrorism charges though, as US officials purportedly “had not established that the Bosnian and Chechen recipients of BIF aid were engaged in a federal crime of terrorism.”

We are thus left to ponder whether Arnaout’s prosecution was deliberately sabotaged, in order to avoid disclosures that would’ve implicated the CIA in BIF’s activities, and therefore the Bosnian and Chechen wars. It has been confirmed that throughout the former conflict, Mujahideen fighters from the world over were flown into Sarajevo on CIA black flights, and received voluminous US weapons shipments, in breach of a UN embargo. Their presence was fundamental to the Bosniaks’ war effort.

Under the terms of the 1995 Dayton Agreement, which ended that proxy conflict, Mujahideen fighters were required to leave Bosnia. Immediately after it was signed, Croat forces fighting alongside British and American mercenaries in the country began assassinating the group’s leadership to send the Islamists scattering. Some fled to Albania along with their US-supplied weapons, where they joined the incipient Kosovo Liberation Army, another Western-backed entity tied to Al Qaeda, and comprised of religious extremists.

Others were intercepted with the assistance of the CIA, and deported to their countries of origin to stand trial for serious terror offenses. This was perceived as a gross betrayal by the Mujahideen’s senior overseas leadership, which included Osama Bin Laden. It triggered a chain of events that ultimately culminated in 9/11. Several purported hijackers were veterans of Bosnia and Chechnya. As The Grayzone has revealed, at least two hijackers had likely been recruited by the CIA by the time of the attacks.

In a perverse twist, while the expulsion of Mujahideen fighters from Bosnia may have enraged Bin Laden, a French counterterrorism report subsequently concluded this “exfiltration” was highly beneficial for Al Qaeda. Its fighters thereafter became “useful again in spreading Jihad across other lands.” Many headed directly to fight Russia. They reportedly “preferred to go to Chechnya, instead of heading for European states to seek political asylum,” fearing they could instead be deported home to face terror charges.

This makes it abundantly clear that Khangoshvili, the so-called “dissident,” was hardly alone among militants “highly respected by the CIA” who fought against Russia in the Chechen conflicts.

Kit Klarenberg is an investigative journalist exploring the role of intelligence services in shaping politics and perceptions.

Source: The Grayzone

Photo: Zelimkhan Khangoshvili

Scott Ritter: Prisoner swap may be ‘the best that US-Russia relations will be for some time now’. (Sputnik, 08.04.2024)