Solidarity with Ghana represented over a century of identification with the homeland.

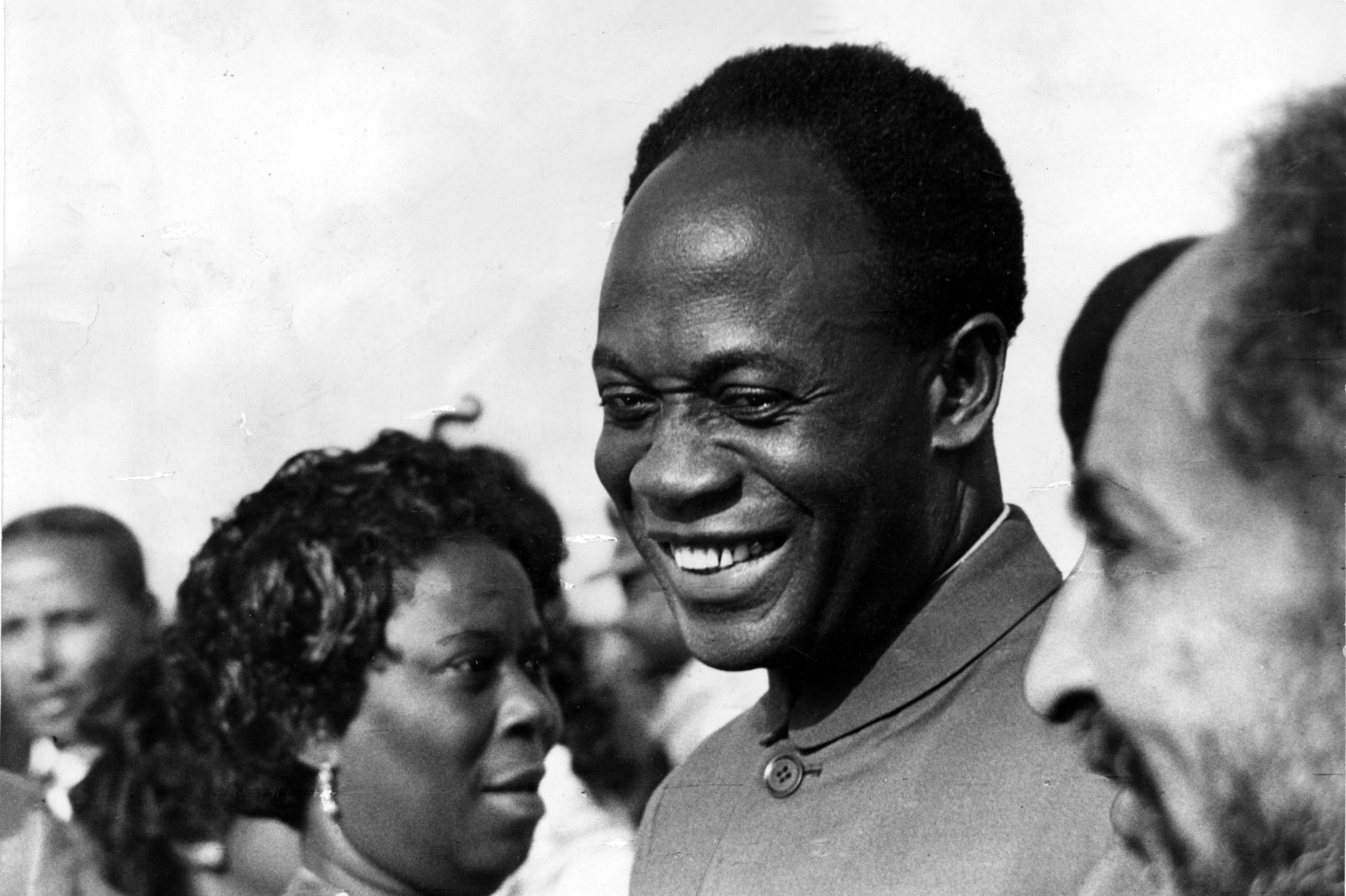

Five decades ago on Feb. 24, 1966, a coup was carried out against Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, the leader of the Ghana independence movement and the chief architect of the 20th century African revolutionary struggle.

Nkrumah, the founder of the Convention Peoples Party (CPP) in 1949, which led the former British colony of the Gold Coast to national independence in 1957, was out of Ghana on a peace mission aimed at bringing an end to the United States intervention in Vietnam. The president had stopped over in Beijing, Peoples Republic of China, for consultations with Premier Chou En-lai and had planned to continue on to Hanoi.

When Nkrumah later met with Chou he informed him that there had been a military coup in Ghana. His initial reaction was disbelief yet the Chinese leader told him that these setbacks were in the course of the revolutionary struggle.

The coup was carried out by lower-ranking military officers and police officials with the direct assistance and coordination by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the State Department. Leading members of the CPP were killed, arrested and driven into exile while the party press was seized along with the national radio and television stations.

CPP offices were attacked by counter-revolutionary mobs encouraged by the CIA and the military-police clique that had seized power. Books by Nkrumah and other socialist leaders were trashed and burned.

Cadres from various national liberation movements who had taken refuge in Ghana and were receiving political and military training were deported by the coup leaders who called themselves the “National Liberation Council” (NLC). Other fraternal allies of the Ghanaian and African Revolutions were fired from their jobs within the government, the educational sector and media affairs.

The CIA involvement was widely believed to be pivotal at the time but in later years firm documented proof was brought to light with the declassification of State Department files which originated under the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson. A letter of protest had been sent by U.S. Undersecretary of State for African Affairs, G. Mennen Williams, to the Ghana embassy in Washington during late 1965 in the aftermath of the publication of Nkrumah’s book “Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism”, which outlined the central role of Washington and Wall Street in the continuing underdevelopment of Africa.

Nkrumah and African American History

Kwame Nkrumah was born in the Nzima region of Ghana at Nkroful in 1909. He would later travel to the U.S. in 1935 to pursue higher education at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the first Historically Black College and University (HBCU) in the country founded during slavery in 1854.

Lincoln was an ideal atmosphere for Nkrumah who studied the social sciences, philosophy and theology. He became involved in the African American struggle through work with the African Students Association where he served as president for several years as well as the Council on African Affairs with Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, Dr. William A. Hunton and Paul Robeson.

He became a licensed Presbyterian clergyman giving him access to speaking engagements in numerous African American churches. Nkrumah worked during his college days doing odd jobs and experiencing severe economic deprivation.

Leaving the U.S. in 1945, Nkrumah settled in Britain for two years where he helped organized the historic Fifth Pan-African Congress at Manchester in October of that year. The gathering was chaired by Du Bois and enjoyed the participation of other leading figures within the African liberation movements including George Padmore of Trinidad, who had worked with the Communist International during the late 1920s and early 1930s; Amy Ashwood Garvey, the first wife of Marcus Garvey, who held left-leaning politics; Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya; along with representatives of trade unions, farmers’ organizations and students.

After Nkrumah returned to Ghana in late 1947 and with the founding of the CPP less than two years later, he would land in prison twice for organizing against British imperialism. Due to his party’s mass support during a colonial-controlled reform election in February 1951, Nkrumah was released from prison and appointed Leader of Government Business as part of a transitional arrangement towards independence won later in March 1957.

During the independence period Ghana became a haven for African American political figures, artists, professionals and business people. Some within this group became staunch defenders of the Nkrumah government which was under increasing pressure from the CIA and the State Department after 1961.

Several hundred African Americans took up residence in Ghana including Maya Angelou, a writer, dancer and supporter of African liberation movements; Alice Windom of St. Louis, a social worker and educator who helped organize the itinerary of Malcolm X when he travelled to Ghana in May 1964; Vicki Holmes Garvin, a labor activist and member of the Communist Party served as a co-worker with Robert and Mabel Williams in China several years later after leaving Ghana; Julius Mayfield, a novelist and essayist who left the U.S. amid the attacks on Robert Williams, worked in Ghana as a journalist and editor of African Review, a Pan-Africanist journal in support of the CPP government; W.E.B. Du Bois was given Ghanaian citizenship and appointed as the director of the Encyclopedia Africana; Shirley Graham Du Bois, the second wife of Dr. Du Bois, a political organizer, member of the Communist Party, prolific writer and producer, was appointed by Nkrumah to head Ghana National Television; among others.

After the coup in February 1966, most of the progressive African Americans were forced to leave Ghana due to the pro-imperialist character of the NLC regime. Dr. Du Bois had died in August 1963. However, his wife who worked as a leading figure in the Ghana government was placed under house arrest by the military-police officials. Shirley Graham Du Bois left Ghana and later lived in Egypt and China where she died in 1976.

U.S. Imperialism Continues Destabilization of Africa

Five decades later the CIA and State Department are still heavily engaged in destabilization of African states and progressive movements. The U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), founded in 2008, is constructing airstrips, drone stations and military bases in various regions across the continent. The anti-imperialist struggle in regard to interventions in Africa is just as relevant today as it was in 1966.

African American political organizations played a key role in influencing Nkrumah from the 1930s, until his removal from power in 1966 and beyond, right up until his death in 1972 in Romania. Although the overthrow of the Nkrumah government was designed by U.S. imperialism to halt the advance of the African Revolution and the internationalization of the struggle of African Americans, solidarity efforts accelerated from the late 1960s through the 1990s when the last vestiges of white-minority rule were eliminated in South Africa and Namibia.

Younger generations of African American activists can gain much from the study of the intersection between the struggle for liberation inside the U.S., the Caribbean, Latin America, Europe and the African continent. It was during this period after the conclusion of World War II and extending to the beginning of the 21st century that tremendous gains were won in the areas of national liberation, Pan-African unity and socialist-orientation.

Today with a strong emphasis being placed on the demonstrations against the use of lethal force against African Americans by the police and vigilantes, identification with broader struggles taking place within the African world are often overlooked. Despite the ideological advances of the previous period where people of African descent began to identify as African Americans, there appears to be an uncritical reversion back to a U.S.-centered approach resurrecting “blackness” in contravention to notions of an “African Personality and Pan-Africanism” advanced by Nkrumah and his collaborators.

These developments, if gone unchecked, will break off the African American movement from its most natural allies among like-minded forces within the entire African world. In addition, with a lack of emphasis on internationalism, the African American struggle will be hard pressed to reach its full potential through winning allies throughout the world.