Today is a day to celebrate the prophetic voice and witness of Fr. Daniel Berrigan, the non-violent anti-war activist and poet, whose life and witness has touched so many lives. He was born on May 9, 1921 and would have been 100 years old today. He died five years ago, but his spirit continues to animate and inspire so many others. The following essay is from my recent book, Seeking Truth in a Country of Lies.

Radical dissidents and prophets have never had an easy time of it. When alive, that is. Once safely dead, however, honors and respect are often heaped on their heads. The dead can’t talk back, or so it is assumed. Nor can they cause trouble.

Jesuit priest Fr. Daniel Berrigan was one such man. When he died on April 30th, the major media, organs of propaganda and war promotion, noted his death in generally respectful ways. This included The New York Times. But back in 1988 when Daniel was a spry 68 years old, the Times published a review of his autobiography, To Dwell in Peace, which was a nauseating hatchet job aimed at dismissing his anti-war activism through the cheap trick of psychological reductionism and reversal.

How could Berrigan really be a Christian, a man of peace, the reviewer Kenneth Woodward (himself a product of eight years of Jesuit education) asked rhetorically, and be so angry? Wasn’t he in truth a bitter, ungrateful, and angry – i.e. violent – “celebrity priest” masquerading as an apostle of peace? And therefore, were not his peace activities, his writings, and his uncompromising critique of American society null and void, the rantings of a disturbed man? Furthermore, by the unspoken intentional logic of such an ad hominem attack, were not those who follow in his footsteps, those who hear his words and – God forbid! – take them seriously, were not they too wolves in sheep’s clothing, angry children trying to exact revenge on their parents? “Gratefulness, we learn, is not a Berrigan trait,” Woodward concluded in his bilious review of a “pervasively angry autobiography.” “The Berrigans (note the plural usage), it seems, never learned to laugh at themselves.”

Such character assassination has long been one tool of the power elite. Silence or kill the prophets one way or another.

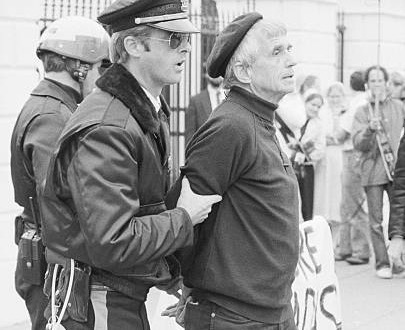

When Dan and I first met we walked together in the blue cold snowy silence of Ithaca nights. It was December 1967. He was a 46 year old black-bereted whirling dervish orbiting a profound spiritual and poetic stillness; I, a 23 year old Marine intent on declaring myself a conscientious objector before my reserve unit was activated and sent to Vietnam.

Dan had been arrested for the first time at a Pentagon demonstration in late October. A few days later his brother, Philip, together with three others, had upped the ante dramatically by pouring blood on draft files in Baltimore. This action, which became known as the Baltimore Four and started a chain of draft board raids over the next years, and the raging Vietnam War that Johnson was dramatically escalating, were the backdrop for my three day visit with Dan. The invitation had been arranged by my inspirational college teacher, Bill Frain, Dan’s friend.

Walking and talking, talking and walking, we whirled around the Cornell campus where Dan was a chaplain, into and out of town, from apartment to apartment, a gathering here, a Mass there. The intensity was electric. At a party I met and learned from the brilliant Pakistani scholar and activist Eqbal Ahmad. At an apartment Mass led by Dan in his inimitable style I felt as if we were early Jewish-Christians gathering in secret. There was a sense of foreboding, as if something would soon break asunder as the U.S. rained bombs and napalm down on the Vietnamese.

I recall a sense of intense agitation on Dan’s part, as if events were conspiring to push him to answer an overwhelming question. I knew from the first that he was no J. Alfred Prufrock who would sit on the fence. He would never say, “I am no prophet – and here’s no great matter/I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker/And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker/And in short, I was afraid.” A poet, yes, a lover of beauty, that I could tell; but I felt his fierceness from the start, and it was something I viscerally connected with. He was preparing for a great leap into the breach; was Odysseus readying to leave Ithaca, not for Troy to wage a violent war, but a peaceful Odysseus readying to leave Ithaca to travel to Vietnam to wage a non-violent war against war – a lifelong journey. I too felt that my life would never be the same and I was venturing out onto unchartered waters. His courage rubbed off on me.

In those few days with Dan I unlearned most of the lessons my Jesuit education had instilled in me. Deo et Patria were rent asunder. I had never accepted the Marine slogan that “my rifle is my life,” nor had I fully ingested the Jesuits’ conservative ideology – what Dan called “consensus, consensus” – that I should become a man successful through speaking out of both sides of my mouth and serving two masters. But at that point I had no Jesuit mentor who embodied another path. In Dan I found that man, or he found me.

Contrary to some public images of him, he was a man of indirection as well as bluntness. He had the gift of discernment. Not once during my initial stay with him did he suggest a course of action for me. We talked about the war, of course, of his brother Phil’s and others’ courage, but we also talked of poetry and art, of the beauty of starry winter nights and the dramatic waterfalls surrounding the Cornell campus. Most of all he wanted to know about me, my family, my background; he listened intently as if he were contemplating his own past as well, weighing the future. I had already decided to leave the Marines one way or the other, but we never discussed this. He arranged for me to speak to a Cornell lawyer who did anti-war work in case I needed legal help. But I felt I was in the presence of a man who knew and respected that such momentous decisions were made in solitary witness to one’s conscience. I felt he supported me whatever I did.

When I set sail from Ithaca I felt blessed and confirmed. I would never go to war; I knew that. But I also came away with a different lesson: that not participating in the killing wasn’t enough. I would have to find ways to resist the forces of violence that were consuming the world. They would have to be my ways, not necessarily Dan’s. I was unyielding in my conviction that I would not stay in the Marines no matter what the consequences; but after that I would have to choose and take responsibility for what Dan referred to as “the long haul” – a lifelong commitment to the values we shared. But values are probably too abstract a way to describe what I mean. Dan conveyed to me through his person that each of us must follow his soul’s promptings – there was no formula. I was young enough to be his son, and yet he spoke to me as an equal. Despite his adamantine strength of purpose and conviction, he let me see the scarecrow man within. No words can describe the powerful stamp this set on my heart that has never left me.

Less than two months later the TET offensive exploded, and Dan was on that night flight to Hanoi with Howard Zinn to bring back three US airmen who had been shot down while bombing North Vietnam. Then the great anti-war leader, Martin Luther King, was executed by government forces in Memphis. The message sent was clear. Shortly Dan was invited by Philip to join the Catonsville action. He gave it prayer and thought, and then jumped in, knowing that the children he had met in the North Vietnamese bomb shelters hiding from American bombs were pleading with him. He later wrote of holding a little boy.

In my arms, fathered

In a moment’s grace, the messiah

Of all my tears, I bore reborn

A Hiroshima child from hell.

He was a changed man. No longer just a priest-poet, he would now become a revolutionary anti-war activist for life. He wrote in “Mission to Hanoi, 1968.”

“Instructions for return. Develop for the students the meaning of Ho’s ‘useless years.’ The necessity for escaping once and for all the slavery of ‘being useful.’ On the other hand, prison, contemplation, life of solitude. Do the things that even ‘movement people’ tend to despise and misunderstand. To be radical is habitually to do things which society at large despises.”

Shortly after Catonsville I was privileged to be invited by Bill Frain to a meeting at his house in Queens, New York of the Catonsville Nine. We met deep in his backyard, huddled in a circle away from the prying eyes and listening devices of the FBI. There my education continued. In January I had submitted my request to be discharged from the Marines as a conscientious objector. Now I was gathering with nine incredibly courageous Americans who had taken personal responsibility for the nation’s war crimes in an act that sent shock waves around the world. Although I don’t recall feeling it at the time, I now realize how blessed I was to have been allowed into that august company. For them to have trusted a 23 year old whom eight of them had never met takes my breath away. I am sure Dan gave the okay.

Later that night I drove him back to where he was staying in Yonkers. So true to form, as we crossed the Whitestone Bridge in the dark, this beautiful man spoke of the exquisiteness of the sparkling lights and the illuminated Manhattan skyline. He was a hunger artist for beauty. And we talked again of poetry and family, of our relationships, how important they were, and how fractious relationships could get when one stood up for truth and victims everywhere. He asked about my girlfriend: what did she think about these things? I sensed that without being explicit he was warning me, while simultaneously telling himself that he was in for some sharp criticism from people close to him. As we rolled along in that cocoon of intimate talk, I again realized how rare this man was, how multi-faceted and deep.

Afterwards, as I drove home, I kept thinking of the great novel by Ignazio Silone, Bread and Wine, a book Bill Frain had introduced me to; of Pietro Spina, the revolutionary in hiding disguised as a priest, and his former teacher, the priest Don Benedetto. Hunted and surveilled by Italy’s fascist government, they secretly meet and talk of the need to resist the forces of state and church collaborating in violence and suppression. Dan and the others had dramatically confronted these twin ogres and were willing to face the consequences. My problem was that Dan was both the revolutionary and the priest, but I was neither. Who was I? The meaning, if not the exact words, of Don Benedetto came back to me: “But it is enough for one little man to say ‘No!’ murmur ‘No!’ in his neighbor’s ear, or write ‘No!’ on the wall at night, and public order is endangered.” And Pietro: “Liberty is something you have to take for yourself. It’s no use begging it from others.”

A few days later another conspiratorial murder took place as Bobby Kennedy was murdered in Los Angeles. First King, then Kennedy. Again I heard Don Benedetto’s words: “Killing a man who says ‘No!’ is a risky business because even a corpse can go on whispering ‘No! No! No!’ with a persistence and obstinacy that only certain corpses are capable of. And how can you silence a corpse?”

Then the police riots at the Democratic convention followed. Fascist forces had been unleashed. The Trial of the Catonsville Nine took place in October, and of course they were convicted – sentenced as Dan so famously put it, for “the burning of paper instead of children.” That fall I received a letter from Marine Headquarters in Washington D.C. informing me that I was being released from the Marine Corps so I “could take final vows in a religious order.” It was a complete fabrication since I was engaged to be married, but it was a way to get rid of me without honoring my request as a CO. Yet in its weird way it was true: I was religious and I was trying to follow an order, but as one of the dissenters led by Dan and his brave companions who formed a different corps – one dedicated to life, not death.

In 1970 when Dan had gone underground instead of reporting for prison, I travelled to the big antiwar event, “America is Hard to Find,” at Cornell. Word had gone out that Dan would appear, which he did in Barton Hall in front of a crowd of 15,000, including the FBI who were ready to pounce on him. When Dan appeared on stage and gave a moving speech about the need to oppose the war, silence and a sense of held breath filled the hall. When he finished to thunderous applause, the lights went out and when they came back on he was gone. It was like being at a magic show. He had escaped inside a puppet of one of the twelve apostles – oh what great joy and laughter! A circus act! Puckish Dan, imaginative through and through, irreverently funny, later said, “I was hoping it wasn’t a puppet of Judas.”

That was the man.

Once my wife and I were eating dinner with him at the 98th St apartment where he lived with other Jesuits. The conversation turned to Dorothy Day, the founder of The Catholic Worker and long-time pacifist and servant of the poor. Day had been a mentor to Dan. I told him how I had followed his example when I was teaching in Brooklyn and brought my students to The Catholic Worker to meet with Day. Now that Day had died, we asked, what would be the Catholic Church’s attitude toward this great dissident? I said that I thought the church would eventually declare her a saint now that she was safely dead. Dan strongly demurred; that would never happen, he said, she was too radical and the institution would not recognize her. Now that Day is being considered for canonization – i.e. declared a saint – I can’t help think of the ways the powers-that-be, both ecclesiastical and secular, have characterized him before and after his death. Is irony the right word?

I return to a question he had the effrontery to ask, not as an academic exercise but as an existential question demanding a living answer: “What is a human being, anyway?” It is the type of question asked by Emerson and Thoreau, Gandhi and King, dead sages all.

In the truest sense he answered that question with his life. A human being is not cannon fodder, a human being is not a piece of paper, not an abstraction, a human being is not a human being when forced to wage war or live off the spoils of war, a human being is not a human being when in the grip of “Lord Nuke.” None of these. A human being is a child of God, and as such is called to resist the rule of death in the world, to resist violence with love and non-violence. A human being is a lover.

This means a human being is necessarily at odds with the powers-that-be, the governments and corporations that in the name of peace prepare for and wage war. It is a view of human being that is bound to be unpopular, except when it can be affirmed with pieties but contradicted by actions

Sainthood is a piety, the kiss of death bestowed as a guilt offering by authorities lacking authority. It is the Judas kiss – a cosmic joke made to make God laugh.

Dan wasn’t a saint. He was something more – a man – a brave, brilliant, and prophetic inspirational dissident, full of contradictions like us all. He was a true human being of the highest sacramental order – flesh and blood, bread and wine, life and death. At the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, when social panic consumed the nation and people, including the institutional churches, shunned gay men as lepers, only a man of supreme non-judgmental compassion would have befriended and cared for dying patients, as Dan did for many years. This didn’t attract headlines as his anti-war activities did, but it symbolized the man. He was a genuine Christian.

Today, he is in death what he was in life – a great spiritual leader. Ever faithful, he leads us on, by deeds and words. There are no bars to manhood (or womanhood), he once wrote. Freedom is our birth-right.

This mess of mythological pottage, this self-contradictory dream, makes slaves of us,” he wrote, “keeps most of us inert and victimized, makes hostages of our children as well as ourselves. And yet we are instructed by the highly placed smilers to keep smiling through, as if the dollars in our pockets or the brains in our heads were still workable, negotiable, a sound tender. As though, in plain fact, our world was not raving mad in its chief parts. And driving us mad, as the admission price to its Fun House.

On the afternoon of April 30, I was cleaning out files and had emptied two large drawers of papers. I noticed there was one green sheet left in one drawer. It was a saying Dan had sent to me about death. “Though invisible to us our dead are not absent.” I thought how true that was and wondered when Dan would die, knowing he was failing.

The next morning I was informed that Dan had died the previous day. The presence of his absence struck me forcibly. It consoles me in my sadness, as I know it does so many others.

On the morning of his funeral, there was a march around lower Manhattan in his honor. Outside the Catholic Worker someone asked me to carry a large photo of Dan, circa 1968. As we proceeded through the rainy streets, it dawned on me that we were walking together again, and although I was now carrying his image, he had carried me for so many years as that indelible stamp on my heart. When I emerged from a coffee shop after urinating, some marchers laughed at the incongruous sight of Dan’s photo and me. I pointed to Dan’s photo and said, “He really had to go.” I think I heard Dan laugh and say, “That’s the way to shirk responsibility.”

I believe he walks beside us still, or in my case, he walks before me, beckoning me on, since I have such a long way to go to learn the lessons that he first taught me long ago on those snowy night walks through Ithaca.

No, you can’t silence certain corpses.

Source: Edward Curtin