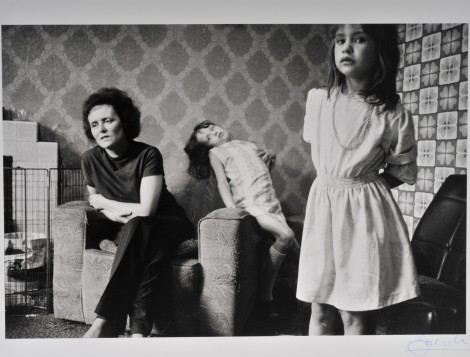

When I first reported on child poverty in Britain, I was struck by the faces of children I spoke to, especially the eyes. They were different: watchful, fearful.

In Hackney, in 1975, I filmed Irene Brunsden’s family. Irene told me she gave her two-year-old a plate of cornflakes. “She doesn’t tell me she’s hungry, she just moans. When she moans, I know something is wrong.”

“How much money do you have in the house? I asked.

“Five pence,” she replied.

Irene said she might have to take up prostitution, “for the baby’s sake”. Her husband Jim, a truck driver who was unable to work because of illness, was next to her. It was as if they shared a private grief.

This is what poverty does. In my experience, its damage is like the damage of war; it can last a lifetime, spread to loved ones and contaminate the next generation. It stunts children, brings on a host of diseases and, as unemployed Harry Hopwood in Liverpool told me, “it’s like being in prison”.

This prison has invisible walls. When I asked Harry’s young daughter if she ever thought that one day she would live a life like better-off children, she said unhesitatingly: “No”.

What has changed 45 years later? At least one member of an impoverished family is likely to have a job – a job that denies them a living wage. Incredibly, although poverty is more disguised, countless British children still go to bed hungry and are ruthlessly denied opportunities.

What has not changed is that poverty is the result of a disease that is still virulent yet rarely spoken about – class.

Study after study shows that the people who suffer and die early from the diseases of poverty brought on by a poor diet, sub-standard housing and the priorities of the political elite and its hostile “welfare” officials – are working people. In 2020, one in three preschool British children suffers like this.

In making my recent film, ‘The Dirty War on the NHS’, it was clear to me that the savage cutbacks to the NHS and its privatisation by the Blair, Cameron, May and Johnson governments had devastated the vulnerable, including many NHS workers and their families. I interviewed one low-paid NHS worker who could not afford her rent and was forced, to sleep in churches or on the streets.

At a food bank in central London, I watched young mothers looking nervously around as they hurried away with old Tesco bags of food and washing powder and tampons they could no longer afford, their young children holding on to them. It is no exaggeration that at times I felt I was walking in the footprints of Dickens.

Boris Johnson has claimed that 400,000 fewer children are living in poverty since 2010 when the Conservatives came to power. This is a lie, as the Children’s Commissioner has confirmed. In fact, more than 600,000 children have fallen into poverty since 2012; the total is expected to exceed 5 million. This, few dare say, is a class war on children.

Old Etonian Johnson is maybe a caricature of the born-to-rule class; but his “elite” is not the only one. All the parties in Parliament, notably if not especially Labour – like much of the bureaucracy and most of the media – have scant if any connection to the “streets”: to the world of the poor: of the “gig economy”: of battling a system of Universal Credit that can leave you without a penny and in despair.

Last week, the prime minister and his “elite” showed where their priorities lay. In the face of the greatest health crisis in living memory when Britain has the highest Covid-19 death toll in Europe and poverty is accelerating as the result of a punitive “austerity” policy, he announced £16.5 billion for “defence”. This makes Britain, whose military bases cover the world, the highest military spender in Europe.

And the enemy? The real one is poverty and those who impose it and perpetuate it.

John Pilger’s 1975 film, Smashing Kids, can be viewed here. Follow John Pilger on twitter @johnpilger

Photo: A British family from the film Smashing Kids, 1975. Photograph: John Garrett

Source: John Pilger