We should also, in my opinion, be looking inside the Intraecclesial domain for other motives which might have led Pope Francis to so solemnly receive Paul Kagame and make such an unfortunate series of statements. Those statements could even be considered submission in the face of the psychopathic accusation that this criminal has made against both the church and the entire world; a world which, according to him, abandoned the victims of “the” genocide. It is the same accusation, that of not protecting the Tutsis, with which he and his own justified the assassination of the entire leadership of the Diocese of the Kabgayi Church. It is but one example amongst many and it comes in spite of the fact that, in reality, the staff of that church saved the lives of at least 30,000 people.

Since the very beginning of the colonial era, the Tutsi royal court, using that proverbial Machiavellian cunning to which I have previously referred, was perfectly aware not only of the important power that the church would come to represent in the future (sustained by whichever colonial power might be in control at the time) but also of the need to control it, from within if necessary. Even as early as 1907, a mere seven years after the arrival of the White Fathers, the first missionaries to Rwanda, the King’s Uncle Kabare, who held the real power, encouraged the young Tutsis to enter the Catechumenate and attend school. The response was enormous and resulted in their transformation into the most numerous and zealous of Catechumens and pupils.

At the same time, and very much in the evangelistic style of the age that was so far removed from Jesus of Nazareth’s own personal style, the ecclesiastical hierarchy was seeking to coexist with the oppressive Tutsi elite and convert its Royal Family in the hope that the people would follow it into the rite of baptism. The primate of the Catholic Church, Monsignor Leon Classe, felt true admiration for the Tutsis and their qualities: cunning, leadership etc… C.M. Overdulve, a Dutch Presbyterian pastor who worked in Rwanda from 1961 onwards, explained in his book “Rwanda. Un peuple avec une histoire: “In a letter addressed in 1912 to the missionaries in Marangara, in the centre of the country, Monsignor Leon Classe, primate of the Rwandan Catholic church, reproaches their inclination towards the Hutus as they ran the risk of stirring violent opposition to the Church and Mission amongst the Tutsi leaders. He ordered them from that point onwards to support those leaders and teach The Hutus the Christian virtue of submission”.

The fact that simple missionaries found themselves every day more affected by the suffering of and the injustices committed against the oppressed masses with whom they were in daily contact (and among whom must also be included a great number of Tutsis) and supporting their ever more just claims cannot and must not hide this historic alliance between the Church’s hierarchy and the Royal Court. So we find ourselves, from the beginning, with, in reality, two sectors within the Church. Bernard Heylen, a religious Flemish man from the Brothers of Charity and director of the Butare School Group in the south of Rwanda, where the Tutsi elites of both Rwanda and Burundi were formed, wrote in 1994 after the triumph of the RPF:

“The Mwami (king) Tutsi from Burundi and Rwanda, with their courtiers and their extensive network of chiefs and assistant chiefs were the instruments of the colonial powers. Religious authorities used the same policy. The Tutsi population was generally recognized (and feared) as the ruling class both in Rwanda and Burundi and it was thought that the population could be converted by converting its leaders. As the democratic and social sensibilities of the missionaries and colonial civil servants grew, their repulsion toward the Tutsi feudal systems increased, and prevailed over the opportunistic thinking which had led to their collusion in previous years”.

The official version of the conflict, that is to say, the RPF version, insists that the Church had always clashed with the Tutsis and was instead allied with the Hutus. This is yet another gross falsehood and a truncated version of the truth. One cannot generalize about the fact that some missionaries were indeed close to the oppressed majority and, at the same time as denying any agreement between the Tutsi royal family and the ecclesiastical hierarchy, conclude that the Church had always been anti-Tutsi. The recognized Rwandan historian, Alex Kagame, author of numerous ethnographic and linguistic studies and expert on the intricacies of the Royal Court (having previously been one of its members) roundly contradicts this and many other RPF fallacies expounded by Nicole Thibon. This latter, so-called expert labeled Kagame as a racist Hutu extremist in a pamphlet which one can only assume to have been “commissioned” (“The Church and the Rwandan Genocide”, Diario Público, 23/03/2010).

History presents us with useful information such as the solemn declaration of the twelve high-ranking members of Mutara III Rudahigwa’s court, on the 17th of May 1958, in response to the manifesto of several Hutu intellectuals and activists calling for social change: “One might ask how it is that the Hutus are now calling for redistribution of our common heritage. In fact, our relationship with the Hutus has always been based on serfdom and as such, there can be no notion of brotherhood between us. If our kings conquered the Hutu’s lands by killing their respective kings and submitting them to servitude, how can they now pretend to be our brothers?” After conceding an interview to the Hutu leaders, the Mwami made the following declaration, included by Professor Pierre Erny in his book “Rwanda 1994”:

“A problem has been brought to our attention, and after careful examination, we declare the following: there is no problem. Those who say otherwise should keep silent […]. The entire country has joined in the search for the diseased tree whose only blossom is division. When it is found, it will be felled, uprooted and burnt, so that nothing remains”.

The elimination of the entire Hutu political class is clearly threatened. From that moment onwards, the Belgian and ecclesiastical authorities, who saw that the situation was at an impasse, slowly changed their position. If, at a later stage, certain Hutu leaders developed a policy of exclusion and elimination, it was no more than a reaction to the intimidation initially demonstrated by the monarchy.

Pierre Erny comments on another excerpt from ancient colonial literature: “read today it is worthy of our indignation whilst at the same time demonstrating extraordinarily perceptive powers of observation. At that time, however, it surprised nobody”. It is a text written by the Belgian Governor General, Pierre Ryckmans, published in the magazine “Great Lakes” edited in Belgium by the White Fathers: “The Batutsis were destined to govern. Their mere presence assures them of considerable prestige in the face of the inferior races surrounding them and even their defects serve only to further enhance them. They are possessed of extreme subtlety, they suffer no doubt in their judgment of men, they move amongst cunning and intrigue as if born to it. They are proud, distant, their own men, rarely blinded by anger, they dismiss familiarity, pity is unknown to them, and their conscience is never troubled by scruples. It is unsurprising that the good Bahutus, less cunning, more simple and spontaneous, more trusting, have been subdued without ever showing the least sign of rebellion […]. They share the characteristics of the Bantu race.”

Even as late as 1994, approximately 70% of the 400 native priests were Tutsis. The supposed anti-Tutsi position and attitude of the Rwandan church are just one more example of the fiction that the RPF has used to distort history. Equally fictitious is the supposedly idyllic, centuries-long coexistence between the two ethnic groups lasting up until the moment of arrival of the colonial settlers whose presence will have provoked -they would have us believe- a conflict that was non-existent up until then. These are just two among many similar falsehoods that are pure invention. They make up the endless intrigues of the Tutsi feudal caste and its successors and this false history is propagated around the world by “international experts” and the powerful media of the Tutsi feudal elite’s Western godfathers; godfathers who recognised in this hard-nosed, arrogant and cunning ethnic minority the ideal Gendarmes to defend their colonial interests; just like the original colonists had done before them.

All this historical information allows us to recognize some of the intra-ecclesiastical movements and intrigues and exposes key points that offer an explanation for the recent meeting in the Vatican and the declarations that accompanied it. But it also enables us to understand, a little better still, that which we witnessed in the three previous parts of this article: the biased Papal Petition asking God’s pardon and the prayer in which he begged forgiveness only for the hate of some Hutu members of the Clergy. Their hatred cannot be considered without taking into account where it was born and cannot be understood without taking into account the equally anti-evangelical ancestral attitude of the other side, namely the Tutsi feudal aristocracy with their pride, arrogance, and sense of ethnic superiority…

Further still, that hatred for which Pope Francis begged God’s pardon cannot be understood without also taking into consideration the profound hatred on the other side: that felt for the Hutu commoners, deeply rooted in the hearts and minds of people like Paul Kagame, before whom, paradoxically, Pope Francis begged pardon for those members of the Church who gave in to hatred and violence. Those who have found themselves close to him know him well. Théogène Rudasingwa, ex-Secretary General of the RPF, ex-Rwandan Ambassador to the USA and ex-Chief of Staff to President Paul Kagame, stated in his declaration made in Washington on the 1st of October 2011: ” In July of 1994, Paul Kagame himself told me, with his characteristic cruelty and with great joy, that he had been responsible for the shooting down of the plane.[…]The truth cannot wait until tomorrow because the Rwandan nation is very sick and divided and it can neither rebuild or heal itself on a foundation of lies. All Rwandans urgently need the truth today”. It is a hatred, that felt by Paul Kagame, that he makes no effort to hide and even shares openly. It is the same hatred that led him to shout out, a couple of years ago, in an exalted mass speech that he regretted not having finished off every last one of the hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees in Zaire. Brother Bernard Heylen also wrote in the same article that I cited earlier:

“As a result of having achieved independence in 1962, Rwanda opted for a Republican regime and ( in contrast with Burundi) there appeared a popular consensus to throw out the Chief as part of the revolution. Rwanda had already chosen, after 1959, to definitively become a Republic [The Monarchy was rejected by more than 80% of the votes]. With the help of the Belgian Administration and by means of a revolution, the Hutu majority had managed to expel the Tutsi Administration despite its dominance of the country. The Tutsi refugee colonies of Uganda, Burundi and Zaire all date from this era. It was predominantly Tutsi chiefs and their families who crossed the borders with all their belongings.

This social, economic and political elite remains, nonetheless, an elite both inside and outside its country of origin. In every country the Tutsi refugees arrived in -with the exception of Uganda- they knew how to maintain themselves in a masterful manner and frequently ascended to directorial roles in the social, economic and political arenas in their host countries. Think of characters like Bisengimana and many others in Zaire, of the economic success of Tutsi merchants in Bujumbura and in the elitist ghettos of Nairobi and, later on, in every European and American country.

The drama that is affecting Rwanda today has its roots in a matter of historical chance which saw the Tutsi refugees in Uganda [Paul Kagame and his friends from the leadership of the RPF] ill-treated by successive Ugandan leaders whilst in the refugee camps. The succession to power of Obote, Idi Amin and, later, Obote again meant that, for the refugees, things would go from bad to worse. The Tutsis that had stayed in Rwanda, despite some tense moments and a few local outbursts of racial hatred, found a greater possibility for development in certain areas. Under both Presidents Kayibanda and Habyarimana the Tutsis managed to maintain a strong presence in both private and public sectors.

In contrast, however, the young generation of Tutsi refugees in Uganda grew up steeped in rancor. The image they had of Rwanda was that which they received from fellow family members also living as refugees. As they grew, that image grew with them and, with it, feelings of nostalgia, but also hatred and the desire for revenge. When Museveni, a Ugandan Hima [an ethnic tribe related to the Tutsis] staged an armed revolt against Obote, who had been placed back in power by Tanzania, the young Tutsis from the refugee camps allied themselves enthusiastically to the Hima leader. Henceforth they became the nucleus of the rebel army[…] Museveni became what he is today [the “strong man” of Uganda ] thanks to the help of the Rwandan Tutsi refugees and from that point onwards they had the Ugandan army at their disposal, willing to help them include Rwanda in the dream of a Hima kingdom. If we place today’s conflict in a broader context we are once again back at the struggle for power between the Hamite and Bantu cultures.

When in 1990 the “Tutsi rebels” invaded Rwanda, a masterpiece of “talk and fight” unfolded. The attack itself, well prepared and well armed, was greatly overshadowed by the skillful moves made in a parallel mass-media campaign […]. A campaign of defamation against Rwanda, its President and the Hutu elite was orchestrated in such a grandiose manner that the country -which only a matter of weeks before the attack was still held up as an example of honest development and harmonious coexistence- was now categorized as a murderous, dictatorial regime.

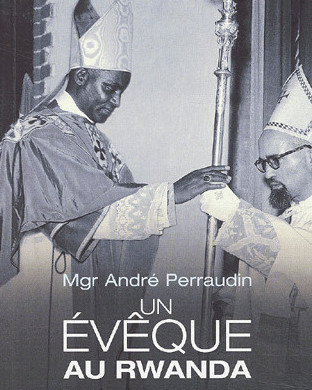

Problems began to arise between the Tutsi courtesan elite and the Church when, coinciding with the years preceding the Second Vatican Council -years that saw a desire to return to source and an attempt to implement the necessary reforms in order to make it possible- the Church carried out an authentic Evangelical conversion led by an authentic prophet: the new Apostolic Vicar, André Perraudin. This prophet appears, just like the Jesuit Archbishop of Bukavu, Christophe Munzihirwa, not to have been listened to neither taken into account by the Vatican diplomats who organized the act of atonement to Paul Kagame and the Tutsi people, the only ethnic victims -or so it would appear- of “the” genocide. James Gasana, Rwandan defense minister from 16th of April 1992 to 18th of July 1993, who is universally considered to be a true moderate, produced these lucid analyses in the year 2000 (“A new assault against the Church”, Mundo Negro):

“Can you imagine how, in a battle for power and with ethnicity as the battleground, the Clergy wouldn’t be an important asset? Is it by mere chance that Tutsis constitute 67 per cent of the Catholic Clergy and 90 per cent of the Joseph’s Brothers (Missionary Society of Saint Joseph), thus forming the most important male congregation in the country? […] The murder [carried out by the RPF] of the [three] Catholic Bishops in [Gakurazo] Kabgayi marks the start of an intense effort to denigrate the Church. This exercise is part of an attempt to rewrite the history of Rwanda, with the objective of saying that the Tutsi genocide had been being prepared for decades and that the Catholic Church, presented here as an instrument of Belgian colonial power, had played a role in that preparation. However, this Church pays, not its unreserved support to a Tutsi elite during the Belgian colonial administration, but rather followed a shift, at the end of the 1950’s, towards a social commitment to the poor Rwandans, Hutus and Tutsis alike, who were oppressed by the feudal Monarchy. It was at that time that it began to take into account the demands of the Gospel in the field of social justice. It adopted, moreover, a socially focussed approach that gave it the authority to point the finger at injustice wherever it was discovered.”

The hatred the members RPF felt towards Monsignor André Perraudin was of such intensity that when, on 4 April 1999, by which time he was already an old man, a mass was celebrated in Switzerland giving thanks for his sixty years of priesthood, they disrupted the celebration, submitting him to all kinds of harassment. This hatred began after his Pastoral Letter or Lent Sermon of February 11, 1959. Taking advantage of our world’s ignorance of these historical episodes, the aforementioned Nicole Thibon -she is just one example among so many others- dared to say that “Monsignor Perraudin’s 1957 sermon on charity and his racist Pastoral Letter of February 11 directly provoked the ‘All Saints Massacre’ of 1959 during which civilians armed with machetes burned Tutsis homesteads, leaving tens of thousands of dead and no fewer refugees.” However, the most “racist” lines of the famous sermon and the most “incendiary” statements that, after centuries of exclusion and injustice, a senior representative of the Church, a man wounded by the suffering of the poor, finally dared to make against these powerful and oppressive elites were these:

“In our Rwanda, social differences and inequalities are linked, to a great extent, to racial differences. Wealth, on the one hand, and political and even judicial power on the other, in reality, rest in a significant proportion, in the hands of people of one single race. […] as the Bishop representing the Church […] it is our job to remind everyone of […] the divine law of Justice in Social Charity. This law requires that a country’s institutions are in such a way structured as to genuinely ensure that all its inhabitants and legitimate social groups are guaranteed the same fundamental rights and the same chances of human advancement and participation in public affairs. Institutions that consecrate a system of privileges, cronyism, protectionism, be it for individuals or for social groups, would not be consistent with Christian morality. Hatred, contempt, the spirit of division and disunity, lies and slander are dishonest weapons and severely condemned by God.”

Surprising then that these “experts” who declare such an evangelical Pastoral Letter, that of February 11, 1959, to be racist “forget” the response (cited above) of the Royal Court which truly is deeply racist towards the Hutu intellectuals. It was a response that came just a few months earlier (on 17 May 1958), to the letter from the Apostolic Vicar. We are talking about a misleading campaign intended to criminalize the Church, a campaign that does nothing but criminalizes those who might one day jeopardize the RPF’s hold on power: the Hutu intellectual elite, of which the Clergy forms a fundamental part. Conversely, Monsignor Aloys Bigirumwami, Tutsi Bishop of Nyundo, declared the Lent Sermon of the Apostolic vicar as the work of a “master” and at the same time urged his colleagues to preach the Christian charity talked about in the above-mentioned Pastoral Letter at Easter. Later, they wrote various letters together calling upon the faithful to practice brotherhood and dialogue among all Rwandans, as well as to search for just and peaceful solutions to conflicts.

Some days after, and in response to, the attacks on Monsignor André Perraudin during the celebration in Switzerland on 11 February 1999, James Gasana sent him a letter of support on behalf of the exiled Rwandan Protestant churches. In stark contrast with the public statements made in the recent Papal meeting in the Vatican, and showing them for what they truly are, the letter unequivocally denounces what it refers to as “the immoral exploitation of the tragedy of genocide for the purpose of creating an ethnic monopoly over power”:

“In such a context [refers to the racist posture taken by the monarchy a few months before the Apostolic Vicar’s letter],” the church would have failed in its prophetic duty had it not proclaimed the teaching of the Gospel loud and clear in matters of social justice […].

We, as representatives of the exiled Rwandan Protestant churches, are convinced […] that you have unceasingly condemned injustice and oppression regardless of which group has been practising it. We are aware that, rather working for national reconciliation, the new regime systematically pursues all those who speak out against the serious violations of human rights taking place in Rwanda. In pursuing its aims, this regime uses precisely the dishonest means condemned in your Lent Sermon […]. These means are ‘hatred, contempt, a spirit of division and disunity, lies and slander’. To these can be added the immoral exploitation of the tragedy of genocide for the purpose of creating an ethnic monopoly over power.

We representatives condemn the slanderous campaign launched against such a worthy Apostolic worker as yourself. We praise the Lord for his courage and his commitment to the teaching of divine law and Christian morality and assure him of our fraternal support”.

The continued existence of this intra-ecclesial conflict, which is taking place even within in The Society of Jesus, is not a fanciful supposition on my part: some of us have experienced it directly, and have even received occasional reprimands from a senior official of this congregation from that African region for having put forward a moderate vision of events in number 95 of the CJ Booklets that did not match the official version (“African Great Lakes: ten years of suffering, destruction and death”, Joan Casóliva and Joan Carrero, October 2000). Even more painful a revelation is that during the night that followed the double assassination of April 6, 1994, three Jesuits, who would be killed the next day, were found celebrating the terrible attack. This was made known to me by a Hutu Jesuit who witnessed it directly and was deeply troubled by the sight of such a party.

If racial hatred triumphed over evangelical brotherhood in the hearts of some Hutu Church members, it is not the only sin for which Pope Francis should have asked forgiveness for the Church. That same hatred had its historical roots, the exposure of which led Monsignor André Perraudin to suffer so much persecution: namely the Tutsi feudal aristocracy’s ethnic superiority complex, one which even triumphed over Gospel brotherhood in many ecclesiastical Tutsis. This sense of ethnic superiority is at the heart of the great tragedy that began in the region in October 1990 with the invasion of Rwanda by the heirs of the Tutsi feudal nobility. Seen in this context, the diplomatic Act of making amends to the Tutsi ethnic group in front of the liberator of “the” genocide, Paul Kagame, and the partiality of the Papal declarations, leads to an obvious conclusion: Pope Francis seems to have listened to only one of the aforementioned ecclesial sectors, opted for the least Evangelical amongst them and declared his support for the official, and false, version of the past and present.

With the arrival of Pope Francis’ solemn and biased attempt at reparation, made in front of that criminal Paul Kagame, millions of confirmed Christian Rwandans (such as the Tutsi Déogratias Mushayidi, sentenced to life imprisonment, or Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza, sentenced to fifteen years’ imprisonment, or even their respective families) have reached the depths of gloom and despair. They have been abandoned even by him that is the successor of the self-same Peter who in those very days of passion abandoned his master. And, what is even harder to accept, as it was for Jesus in his final hour, is that they appear to have been abandoned even by the Father. What more terrible thing can happen to them now? But precisely because of this, because they have reached the very heart of darkness, all that is left for them is to wait for the arrival of the light. That light of the risen Lord who, at the end of this very night, Holy Saturday, in this prodigious space-time continuum of Albert Einstein, in this timeless liturgical Today, overcame all lies, all hatred and all death. Their only hope is that, just as happened with Peter’s own betrayal, the momentous error of Pope Francis can become a cause for their salvation. That will be our main prayer at the Easter Vigil that we are going to celebrate in a few hours time. We will celebrate it confident that, given Pope Francis’ delivery to our Lord Jesus echoes that of Peter, this agonizing story is not yet over.

In any case, one thing is certain: the triumph of Truth and Light comes closer every day. We will not have to wait so long to see the fall of Paul Kagame. Right now, thanks to his powerful Western sponsors, he seems invincible. For the time being, the power of the false, official version of “the” genocide of the Tutsi (the only genocide), for which Pope Francis has apologized, prevents the understanding of what really happened. But, sooner or later, Paul Kagame will fall. Just as Rafael Videla fell, as did so many others. And from that moment, an abundance of information about unbelievable atrocities that is currently silenced will come to light. This is the realization and certainty to which Mahatma Gandhi clung in times of discouragement: “When I despair I remember that, throughout history, truth and love have always triumphed. There have been many tyrants and murderers who, for a moment, have seemed invincible, but in the end, they always fell. Keep this present. Always”. One day, the deep satisfaction of those who remained faithful to the noblest of principles will be without comparison. On that day, the discovery that The Path, with all its punishments, was actually the goal, will be truly priceless.